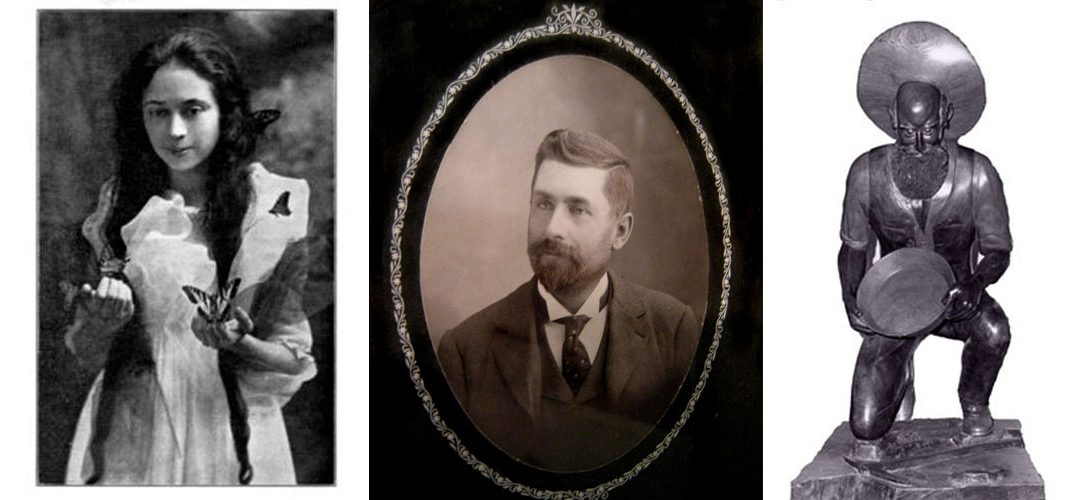

Opal Whiteley

Every town has its legends. Most are unknown to outsiders. However, our legend, Opal Whiteley, is known worldwide. Many visitors come to Cottage Grove each year to see where she lived and wrote about. People love to take selfies by her mural.

In 1918 Opal was the most popular teenager in Oregon. She was a magnetic teacher and youth leader blending science and faith in lectures to thousands of people. She had a nature collection that numbered into the thousands of items. Everyone thought she would be a great teacher or scientist. Instead, she became perhaps Oregon’s most controversial author and the last literary mystery of the 20th century.

It can be hard to separate fact from fiction in legends. We don’t know for certain what her younger years were like, but she came to Cottage Grove in 1904 when she was six years old. Her family’s farm was near today’s Row River Trail Head on Mosby Creek. She was from a family of loggers and miners. Her writings are filled with both her love of nature and the people who work in the woods. Her uncle, Henry D. Pearson was among the first to discover gold in large quantities at the Annie Mine in the Bohemia Mining District. Opal’s father worked in many lumber camps.

By the time she was in high school, Opal had lived in over a dozen lumber camps up and down the Row River. She could hunt, fish and sew her own clothes. She also had a talent for teaching children. Opal was nine years old when she started taking children on nature walks, describing the beauty of the outdoors and inspiring them to love its Creator. She attended the Church of Christ at 6th and Gibbs. In her early teens, Opal gained fame around the state with the Junior Christian Endeavor youth group, increasing its membership ten fold in just a few years.

Opal also caught the attention of the University of Oregon faculty, who admitted her before she had finished high school! She entered the university with the fanfare usually reserved for a sports star today. However, she took a huge load of classes and set the record for most library books checked out. Opal was like the proverbial kid in the candy store! She had a photographic memory, which some researchers have attributed to autism. But Opal dropped out in her sophomore year, leaving many classes incomplete.

In 1918 Opal Whiteley left the university for Los Angeles to pursue her dreams of writing nature books and building a children’s museum. She even tried to get into acting. Opal was unsuccessful at getting into motion pictures, but she did teach the children of many Hollywood stars and producers. They also helped her publish her first book, The Fairyland Around Us. From Hollywood Opal traveled east to Boston, home of the nation’s most influential publishers.

Opal appeared to strike gold. In 1920 her childhood diary, Opal, the Journal of an Understanding Heart was the number two best-seller. At the young age of twenty-two, Opal Whiteley was a major international success! Her story of being an orphaned child growing up in the Oregon lumber camps took the literary world by storm. Opal’s tales of talking with trees, animals and their fairy spirits captivated audiences.

But with the same speed as she rose … Opal fell from the public’s favor. Just a year later her diary was out of print and Opal was accused of fraud, and lying about her family. She claimed that the Whiteleys were not her real parents and that her actual “Angel Father” was a French prince, Henri d’ Orleans. It was also charged she had written her diary as a young adult, not as a child.

Disgraced, Opal went to India and Europe to prove her story. She never returned to Oregon. But today, she is buried in London’s aristocratic Highgate Cemetery under both her French and her American names. Her story of royal birth is more accepted in Europe than in America. You can view a rubbing of her gravestone in the Library.

For decades Opal Whiteley’s beautiful writings about nature, God and children gathered dust – while she was committed to an English mental hospital. The hospital accepted that she was of aristocratic heritage but considered mentally ill. She died there in 1992 – locked away for almost fifty years, diagnosed with schizophrenia, although it’s more likely she was on the Autism Spectrum. Opal Whiteley’s work and writings were almost forgotten.

Today, Opal has made a literary comeback. Her books have been reprinted in at least four languages, including French and Chinese. There is a nice tourist map of the places where Opal lived and wrote about. Statues of Opal stand at the entrances of both the Cottage Grove Library and the University of Oregon’s Knight Library. Oregon’s college dropout now greets visitors at two libraries. (That must make her some sort of princess.)

Even after 100 years there is controversy – “What Happened to Opal?” Different people see her differently – like the opal gemstone itself. If you like a good mystery or enjoy enchanting descriptions of nature, then explore the story of Opal Whiteley. The Opal Whiteley Memorial is the largest site on the Internet for research, photos and unpublished pieces of her diaries.

Dr. G.O. Snapp

The house bears the name of one of Cottage Grove’s first physicians, Dr. G.O. Snapp. The doctor built the house to serve as his residence and office. He lived there with his wife. The home has ornate exterior gingerbread features and a tall spire called a “witch’s hat” atop the front entrance. It’s a one-story house with 12.5 foot high ceilings throughout its interior and is decorated in period style.

An early advertisement in an 1899 issue of the Bohemia Nugget identifies Dr. Snapp as a physician and surgeon, who also extracted teeth. There are artifacts inside the house that tell more of the story of the early and colorful doctor who served patients in Cottage Grove around the turn of the last century.

The Story of Bohemia Johnson

The man who discovered the gold in 1863 and started the gold rush was named James Johnson, and he had the nickname of Bohemia. He was born in Missouri in 1830, and when he was 30 years old he had moved to Ashland, and working on a farm. In the 1860 census he listed his occupation as “miner” although he was living on another family’s farm and was probably a farm hand and mining in his spare time. In 1863 Mr. Johnson and his partner George Ramsey, who also listed his occupation as a “miner” had traveled to Roseburg. Here in Roseburg one of the two got into a fight and killed an Indian, and they both went on the run up the North Umpqua River. They followed the river until they came to Steamboat creek, and then they followed Steamboat creek until they came to City creek. Then they followed City creek up to its headwaters which is in the heart of the Bohemia mining district. Here, close the headwaters of City creek, James Johnson killed a deer and while dressing out the animal he looked down and saw a very rich piece of gold bearing ore.

It’s a certainty that he didn’t show this to his partner George Ramsey because Mr. Ramsey doesn’t appear on any of the mining claims and after this point is completely out of the picture.

James Johnson filed a total of 12 mining claims between the year 1867 and 1869 and they are still on record in the Douglas county archives. We speculate that in 1864 Mr. Johnson spent the summer prospecting and laying out the monuments for his mining claims. In 1865 he returned with nearly 40 men, some of which were his new partners, in order to firmly establish which parts of the area he had laid claim to. For around two years nobody was putting any of the nearly 180 mining claims to paper, until Douglas county sent a clerk up to the area to begin recording the claims.

Mr. Johnson began recording his claims in August of 1867, and the one that made him the most money was called the Excelsior. A few months after he filed on the Excelsior he turned around and sold it to Steven F. Chadwick who would eventually become Oregon’s 5th governor. Mr. Chadwick who was a Douglas county judge at the time, and his son Baker, paid Mr. Johnson $1500.00 for the Excelsior, which at the time was the equivalent to a couple million dollars. Mr. Johnson eventually sold the remainder of the Excelsior claim to Joseph Knott for $250.00 who installed a stamping mill and began processing the gold. There’s hand written documents for both of these sales in the Lane county archives and on the signature line on each of them James Johnson signed his name with an X. He evidently was illiterate (as many people were at the time), but by the way he handled his business affairs it’s apparent that he was a shrewd individual.

After this point there is no more mention of Bohemia Johnson in any of the records and it’s assumed that he left the area.

Mining historian Ray Nelson said that James Johnson sometimes went by the name of John. Also, there was an obituary found at the Cottage Grove Genealogical Society for a man with that same name that was born in the correct year. The obituary said he was a wealthy miner from Cottage Grove and he died in Denver Colorado in 1905. His probate took place in Chaffee County Colorado at which time Mr. Johnson’s widow took possession of a house at 1653 Main Street in Cottage Grove. There is much circumstantial evidence pointing to this man as being our Bohemia Johnson, however, there is nothing definitive, or no solid proof that he was the same man. So we may never know for sure what happened to the man who had such a monumental impact on our town.